Book of Trees: Thistle and Pearl (5)

Chapter 5: Salem Witch Trials, 1692 // Lost letters // Saint Margaret’s book // Family patterns // Milk Thistle Tea

Quick recap: Last week, I wrote about George Jacobs Jr., my 7th great-grandfather, an accused witch, who in 1692 abandoned his mentally ill wife, his elderly father, and his young children. This week: his daughter Margaret’s story.

THE MYSTERY:

Margaret Jacobs is my sixth great-grandmother. To me, she is the most fascinating and heroic figure from the Salem Witch Trials. Most of her story remains hidden, but her voice comes through in two long-lost documents.

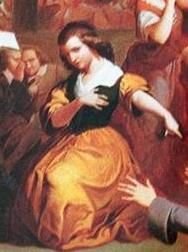

The painting below depicts the witch trial of George Jacobs, Sr., where he testified that he was as likely to be guilty of being a wizard as of being a buzzard. (More on him next week.)

Trial of George Jacobs, August 5, 1692, by Thomkins H. Matteson, 1855

This figure represents his granddaughter, Margaret, pointing at her grandfather, accusing him of witchcraft.

Not her best moment.

…

To get the whole picture, let’s go back to Margaret’s mother, Rebecca.

Rebecca Andrews was born on April 18, 1646, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her father died when she was one year old.

When she was 26, her husband, a weaver named John Frost, died suddenly, leaving her with three children under age six and a weaver’s loom.

In (freezing cold) Colonial America, a loom was invaluable. But women were not allowed to participate in skilled trades.

Rebecca was not permitted to operate the loom to support her family.

She remarried within four months to George Jacobs Jr., who was three years younger and had no profession.

They would have six more children together.

Historian Charles Upham wrote in 1867: "…the affair of drowning the horses was probably for a long time a topic of gossip,

Upham was among the historians who observed a pattern in the witch trial accusations: many of those accused were enemies of the Putnam family. In 1692, the Putnams would ruin the Jacobs.

His most concise volume was Salem Witchcraft in Outline. (1891)

Various records show that Rebecca exhibited signs of mental illness around 1680, when Margaret was five years old.

I can only speculate based on the existing records. To me, it appears likely that Rebecca’s son, John, born in 1679, did not survive infancy. After John, Rebecca had three more children over the next four years. In 1685, her daughter Mary (age 2) drowned in a well on the Jacobs property.

As I wrote last week, Rebecca’s arrest was so heartbreaking that later descriptions of it led to the Dean of Harvard losing his career. Rebecca spent long months shackled and hungry in prison. She began to cry out that she had killed her baby, Mary.

When Rebecca was arrested on May 14, her daughter, Margaret, had already been in prison for 4 days. Margaret had been living with her grandfather, George Sr. (then around 84), for some time. We don’t know why. Her Grandpa didn’t need domestic help. George Sr. and his wife, Mary, had a live-in indentured servant named Sarah Churchill.

Like other witch trial accusers, Sarah was a refugee from the massacres of King Philip’s War. (for more on that history, please see note #1 below). Sarah Churchill was accused of witchcraft and confessed on May 9, 1692.

In 1831, while researching his first book about the witch trials in the Salem clerk’s office, Charles Upham found evidence that Sarah wanted to recant her confession.

Charles Upham wrote: (edited – full text at the link)

The following piece of evidence is among the loose papers on file in the clerk’s office :

“ The Deposition of Sarah Ingersoll,— Saith, … Sarah Churchill… came to me crying and wringing her hands, seemingly to be much troubled in spirit… She said, in saying she had set her hand to the Devil’s book… because they threatened her, and told her they would put her into the dungeon,… if she told Reverand Noyes but once she had set her hand to the [Devils] book, he would believe her; but, if she told the truth…a hundred times, he would not believe her.

Signed: Sarah Ingersoll. Ann Andrews.

These women we incredibly brave to offer testimony. The courts ignored them.

The court demanded that Sarah Churchill accuse others in exchange for her life. So, she did: George Jacobs Sr. (her employer), George Jacobs Jr. (his son), and Margaret Jacobs (the 16-year-old granddaughter).

The next day, May 10, 1692, Margaret and her grandfather were arrested together.

The Warrant

As I described last week, George Sr.'s examination on May 10, 1692, didn’t go well.

The afflicted girls shrieked and writhed. Ann Putnam, whose family’s horses had been drowned, said George Sr.’s spirit told her he’d been a witch for 40 years.

George Sr. scoffed at the court.

If you accuse me of being a wizard, you might as well accuse me of being a buzzard. I have done no harm.

In a subsequent hearing, Margaret Jacobs was accused.

Once accused, the only way to avoid the death penalty was to confess and reveal the names of other witches you had associated with. The interrogations occurred in crowded rooms after weeks of deprivation in a freezing, filthy dungeon. The shrieking accusations and theatrical performances likely caused the accused to doubt their own sanity. If they raised their hand, the chorus of those afflicted might fall silent, fainting, cold, or scream and show pins that had been stabbed into their hands, drawing blood.

“when she was brought into the room

the afflicted persons fell down…”

Margaret was the same age as these (trauma-bonded, mean-girl) accusers. She also had survived a difficult home life. The pressure on her to accuse her grandfather, because he refused to confess, was enormous.

The court needed her accusation to justify its work because all the evidence was invisible, like the emperor’s new clothes.

I’ve edited her beautiful statement. The complete text is available at: Salem Witch Papers No. 80:

Margaret confessed to witchcraft and accused her Grandfather.

That next day, Margaret recanted.

I’ve edited her beautiful statement. The complete text is available at: Salem Witch Papers No. 80:

She said:

“I was cried out upon by some of the possessed persons, as afflicting them; whereupon I was brought to my examination, which persons at the sight of me fell down, which did very much startle and affright me.

They told me, without doubt I did [afflict them], or else they would not fall down; they told me, if I would not confess, I should be put down into the dungeon and would be hanged, but if I would confess I should have my life; the which did so affright me, with my own vile wicked heart, to save my life… I did, which confession, … is altogether false and untrue.

The very first night after I had made confession, I was in such horror of conscience that I could not sleep for fear the devil should carry me away for telling such horrid lies. What I said, was altogether false... I could not contain myself before I had denied my confession, which I did though I saw nothing but death before me, chusing rather death with a quiet conscience, than to live in such horror...

Where, upon my denying my confession, I was committed to close prison, where I have enjoyed more felicity in spirit, a thousand times, than I did before…”

The Jacobs Home, Salem, MA

Margaret visited her grandfather in prison. She apologized, and he forgave her.

On August 5, George Jacobs Sr. was convicted of witchcraft.

On August 19, 1692, George Jacobs Sr. was hanged.

The next day, Margaret wrote a letter to her father that was never sent. It remained in Salem’s clerk’s offices for nearly 200 years before Charles Upham found it again while sorting through loose court documents.

From the Dungeon in Salem-Prison, August 20. 92.

Honoured Father,

…hoping in the Lord of your good Health, as Blessed be God I enjoy, tho in abundance of Affliction, being close Confined here in a loathsome Dungeon, the Lord look down in mercy upon me, not knowing how soon I shall be put to Death…

But blessed be the Lord, he would not let me go on in my Sins… I confess the truth of all before the Magistrates, who would not believe me, but ‘tis their pleasure to put me in here, and G-d knows how soon I shall be put to death.

Dear Father… send us a Joyful and Happy meeting in Heaven.

My Mother, poor Woman, is very Crazey, and remembers her kind Love to you.

I rest, your Dutiful Daughter,

The full text is here:

She wrote her father to say goodbye.

If Margaret had reversed her position, she would’ve been freed from prison, where she was shackled in irons and avoided execution. She’d have enjoyed a taste of social power, big warm meals, and the company of her celebrated peers.

Margaret’s reversal would have added more legitimacy to the entire fiasco: the cruel accusers, the foolish judges, and the exploitative moralizers. This teenage girl, who had no support system on earth, stuck with the truth, even though it would cost her her life.

I work in academia. Tenured adults are afraid to speak up, for fear of being disliked.

Margaret’s bravery begins with acknowledging her vulnerability. She admits: I got scared and confused, and I lied, and it was wrong.

She writes, "I could not contain myself.” Margaret could not hold a lie in her body.

I wonder about Margaret’s neurology, just as I wonder about her father’s.

Her father, George, seems to have had little conscience. This pattern repeats throughout my family’s history.

The Salem court concealed Margaret’s formal petition to recant until January 4, 1693, after the Governor of Massachusetts ended the trials. He disbanded the court immediately after his own wife was accused of witchcraft.

Margaret and her mother were released from prison months later after they paid their fees.

After her release from prison, Margaret disappears from the records.

She lived another 24 years, becoming a wife and a mother. She died at age 41 on March 22, 1717, leaving eight children aged 4–16. Her oldest was named Rebecca.

I noticed that 1717 was a “mortality cluster” for Salem Witch Trial survivors, including:

Margaret Jacobs (died 1717)

Jonathan Jacobs (her brother) (died 1717)

George Jacobs Jr. (her father) (died early 1718)

Rebecca Andrews Jacobs (her mother) (died 1717)

Uncle Andrews (Margaret’s Uncle) (died 1717)

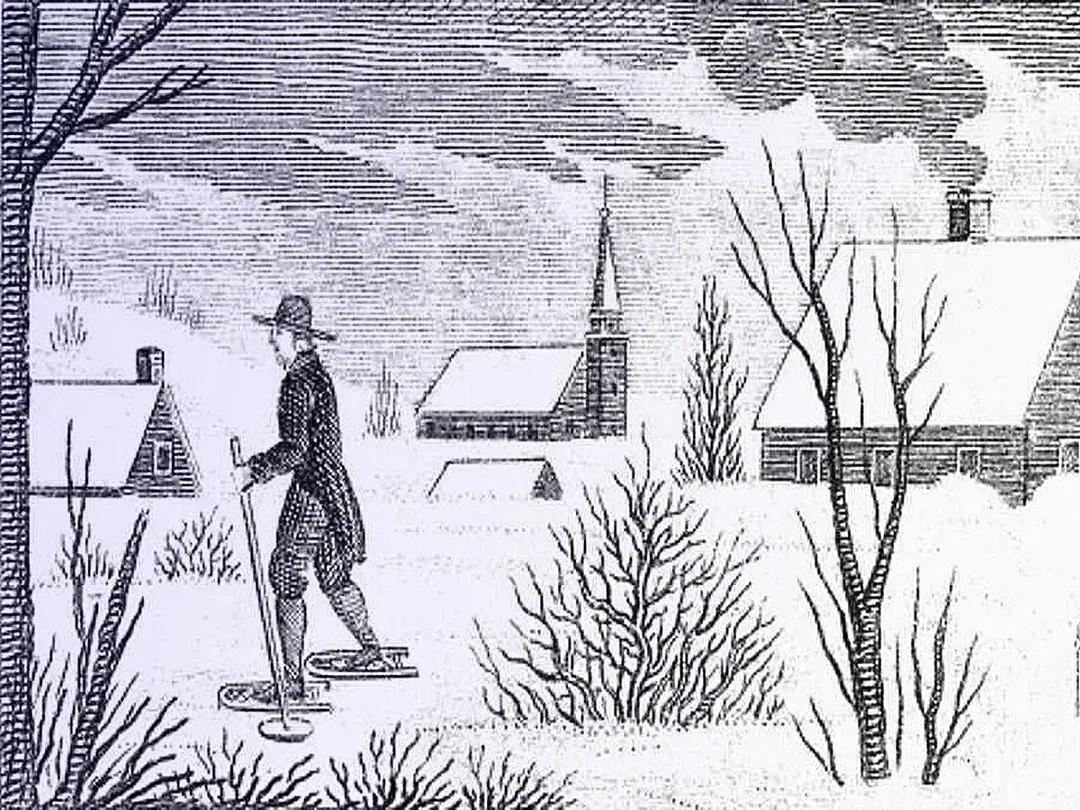

Has anyone else noticed this pattern? The concentration of Salem survivor deaths during the 1717 Great Snow seems significant - but I haven't found it discussed in any scholarship. At least 13 people who participated in the Salem Witch Trials died during or immediately after a weather event called the Great Snow of 1717, causing a 70% mortality spike.

An engraving from the NE Historical Society

Two primary sources report that between February 27 and March 7, 1717, four severe snowstorms occurred over 10 days, with drifts reaching up to 25 feet high. There is documented data on the loss of thousands of livestock, but no studies on the human death toll (yet… anyone interested in a PhD thesis topic?).

After surviving so much, Margaret’s life ended as her world froze into an endless, pearly abyss.

What a courageous teenager she’d been.

Saint Margaret from a medieval family tree c. 15th century.

Margaret Jacobs was named after Saint Margaret, "The Pearl of Scotland."

Saint Margaret of Scotland had a gospel book decorated with jewels.

She dropped it in a stream, fished it out, and it emerged undamaged. This was considered her miracle. The book was lost for centuries, but is now kept at the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

from Saint Margaret’s book

Thistles are Scotland's national flower. Legend says Scottish warriors were saved when a Viking invader stepped on thistles and cried out, alerting the Celts to the attack.

Craft and Practice:

Milk Thistle Tea Recipe:

Milk thistle (Silybum marianum) has been used for over 2,000 years to support liver function (processing toxins) and to support lactation (nourishing new life).

Safety note: Check with a healthcare provider before taking any herbal medications.

What You Need:

· 1 tablespoon dried milk thistle seeds (crushed or ground)

· 3 cups water

· Honey (optional)

· Lemon (optional)

Instructions:

1. Gently crush the seeds with a mortar and pestle. Aim to break them open, not turn them into powder. This releases silymarin compounds that support liver health and aid lactation.

2. Bring water to a boil, then reduce to a simmer.

3. Add the crushed seeds and simmer for 20 minutes. The tea will turn golden-brown.

4. Strain through a fine mesh strainer or cheesecloth. The seeds are prickly even after brewing - handle carefully.

5. Add honey or lemon if desired.

Traditional use for nursing: 1-3 cups daily. Many mothers report increased milk supply within 24-48 hours.

For liver support: 1-2 cups daily.

The Practice:

Make your thistle tea. As it steeps, think back on your life’s relationships. Have you been drawn to more George Jr’s or Margarets?

Pearls form, perfect spheres around irritants in the clam. Spiky thistles nourish new mothers.

What hurts can be a source of stamina and beauty.

Next week: Was George Jacobs Sr. a converso from a long line of healers? His incredible origin story next week.

How Can I Help?

What natural art technique do you want to learn next? Comment with your request—I'll add it to my list for future tutorials.

Have a mystery? My friend and I can help. No charge. We just love a good story.

Find me on Substack: https://enidly.substack.com/

Enid Baxter Ryce is the author of the books Plant Magic at Home, Ancient Spells and Incantations, The Borderlands Tarot, and the forthcoming Grace Flows Through You. Her artwork has been exhibited at the National Gallery of Art, the Getty, and the Library of Congress. She's a professor at CSU Monterey Bay, a fellow of the Sephardic Stories Initiative, and makes her art supplies from plants in her garden.

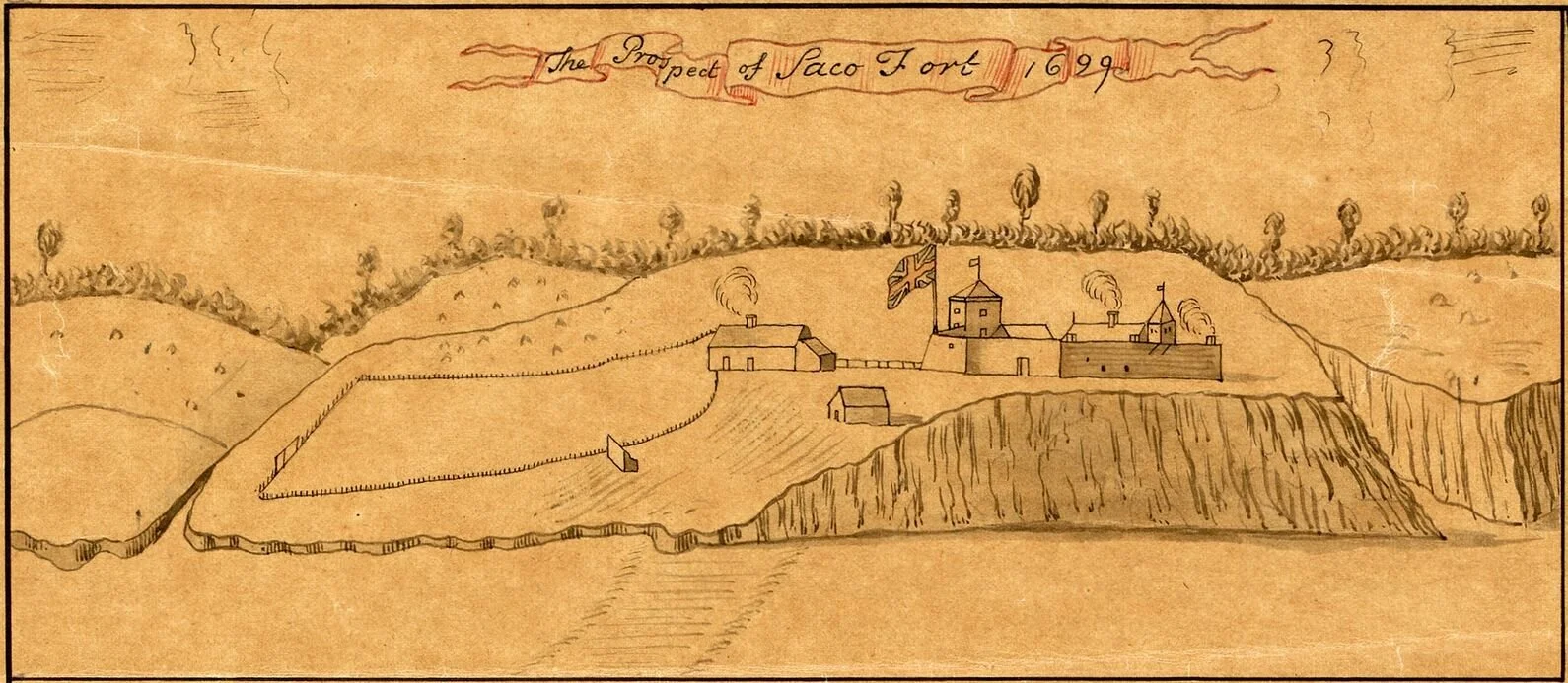

Fort Saco, ME. The Northern Front in three brutal wars.

Note #1: King Philip's War

Note: Before the Revolutionary and French and Indian Wars, three bloody, complex battles raged across the colonies: King Philip's War (1675-1678); King William's War (1689-1697); and Queen Anne's War (1702-1713). In each of these, the French would fight the English, and the Indigenous tribes would choose sides. Women and children were massacred as a matter of course.

When King Philip's War began, Sarah Churchill was about 8 years old and living in Saco, ME. In 1680, Wabanaki fighters attacked her village.

https://archive.org/details/documentaryhisto06main/page/92/mode/2up

Starting in 1675, a series of letters describes the terror that would define her childhood.

By the time the Salem Witch Trials began, Sarah Churchill had survived the war, lost her aristocratic status, and moved to Salem to live as a servant, near her cousin (and fellow accuser) Mary Warren.